100 years of plant nutrition in Hohenheim

Plant Nutrition Institute in the 1930s and today.

The founding of the institute under Margarete von Wrangell (1923 – 1932)

Hunger and bad harvests in the Weimar Republic

It was still in the bones of many. The food rationing after the First World War. Long lines in front of stores were part of everyday life in large cities, because eggs, fish, potatoes, bread, butter or milk were only issued with ration cards. This was necessary because there was a shortage of labor and horses during World War I and the harvests had collapsed. Fertilizers also became increasingly scarce because of the Allied blockade policy, and grain yields fell from 27.1 million tons (1914) to 17.3 million tons (1918).

Diminishing yields led to peak food prices, so that the poorer segments of the population in particular suffered from hunger. Inflation, driven by the Allies’ reparation demands, did the rest to cause food prices to rise immeasurably. Hunger remained omnipresent in Germany until 1924.

No wonder the Prussian government wanted to increase yields and also use science to make itself less dependent on food and fertilizer imports. Thus, in 1923, the Institute for Plant Nutrition was founded at the Hohenheim Agricultural College. Phosphate was one of the three basic components of mineral fertilizers, which, unlike nitrogen and potassium, had to be imported.

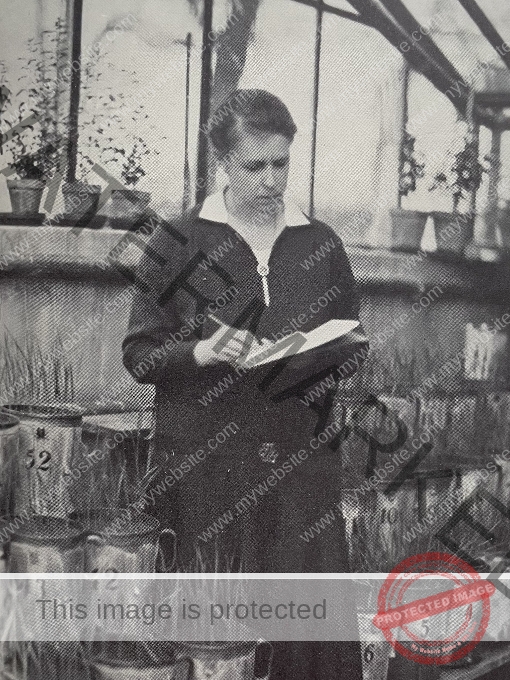

The Chair’s first professor, Margarete von Wrangell, focused her work primarily on the availability of phosphates in the soil. She recognized that certain plants can convert poorly soluble phosphates in the soil into plant-available compounds in the presence of acidic fertilizers.

In order to make use of this knowledge, Margarete von Wrangell and Friedrich Aereboe developed the “Aereboe-Wrangell fertilization system,” the success of which, however, was already highly controversial among agricultural chemists at the time.

Margarete von Wrangell was also very open to new measuring applications. For example, she used a new method to prove that plants do not take soil nutrients from the soil itself, but from the soil liquid.

Despite the high prices during the inflation, her laboratory was always well equipped, which she probably owed to her good network. Only eight years after her appointment, Margarete von Wrangell fell ill with a kidney disease from which she never recovered and died at the age of 55 in the Katharinenhospital in Stuttgart.

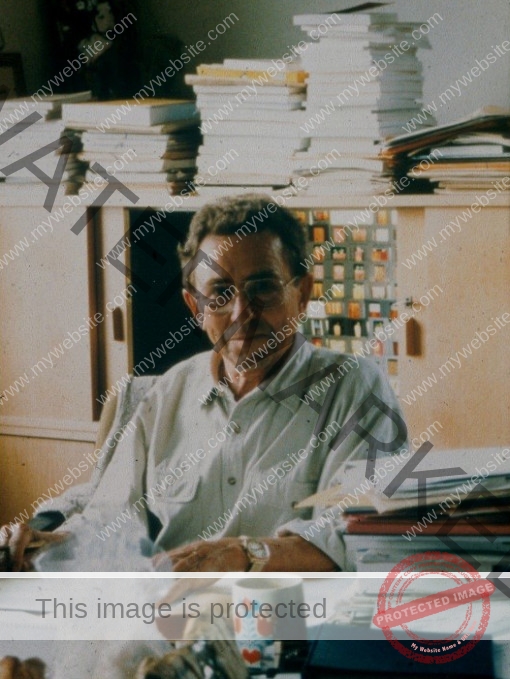

Prof. Margarete von Wrangell 1928

© Photo: Grete Batzke

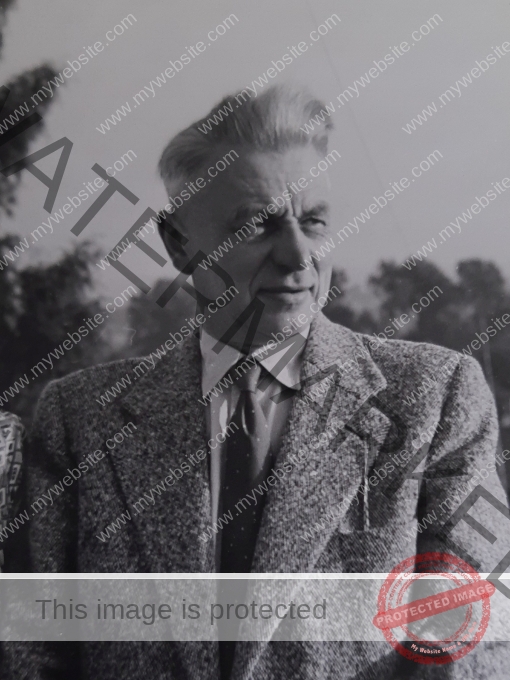

Prof. Maiwald in Hohenheim

The institute under Kurt Maiwald (1932 – 1960)

The battle of production in the world economic crisis

Dung heaps. They characterized everyday life at the institute under Margarete von Wrangell’s successor Kurt Maiwald. In 1932, immediately after her death, he accepted the call to the chair – at that time as a habilitated private lecturer at the University of Breslau – and at the same time took over the management of the institute.

He had become known in professional circles for his international comparative studies; now he was scientifically investigating the effect of manure on plant growth and humus formation. In front of the castle, which at that time also housed the secondary school (forerunner of today’s Paracelsus-Gymnasium-Hohenheim), there was a huge pile of manure that was used for numerous experiments.

Among other things, Kurt Maiwald experimented with the utilization of municipal waste materials such as sewage sludge. And investigated whether prolonged composting helped clean up contaminants such as motor oil.

Just one year after taking office, the Nazi Party under Hitler took power and began to control science and education. They appointed party members to leading positions in the universities and had the then State Secretary in the Reich Ministry of Food and Agriculture declare a “battle of production”. Germany was to become self-sufficient and finally overcome the period of crop failures. However, despite a wide variety of measures and the continuation of the program until 1944, it was not possible to make Germany independent of imports. Thus, the focus of research at the institute shifted from the analysis of nutrients in the soil to substance turnover and crop yields.

After the end of the Second World War, the Allies temporarily banned many professors from teaching as part of the denazification process. This also affected Kurt Maiwald, who was not allowed to teach as a professor from 1948 to 1950. He thus concentrated entirely on his experiments and was called upon to work as an interpreter for the American occupation forces in Stuttgart. From October 1949 to October 1950 he was in Egypt with his family, taught as a visiting professor and was an advisor to the Egyptian government.

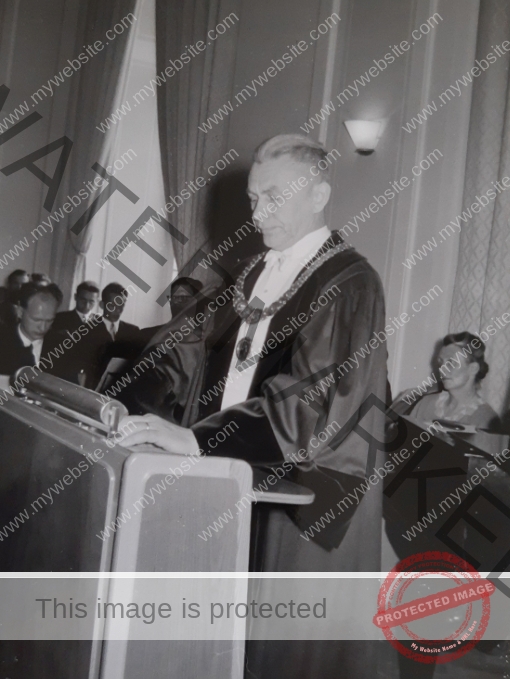

When he returned to Hohenheim, he was appointed rector in 1952. In his inaugural address, he was critical of the traditions of student fraternities. “In agreement (…) the rectors again appeal to the universities, senates and student bodies to do everything possible to prevent arrogant ideas of honor from reviving and making their appearance.” In doing so, he quoted Rector Trillhaas of the University of Göttingen: “The German people no longer want a beer student. It detests them.” And “A national honor will never again be won if we do not finally get out of the atmosphere of wet songs, arrogance, and grandiose immaturity, and in humility also show the other peoples and races the same honor and understanding that we expect from them.”

Prof. Maiwald with his family in Cairo

Prof. Maiwald during his inaugural speech as Rector in Hohenheim

Relationships with other countries had always been important to Kurt Maiwald. But after the wars, these had to be rebuilt slowly – for example, by officially inviting entire groups of students. Under Kurt Maiwald’s leadership, an Iranian and an Egyptian student group came to Hohenheim and the number of foreign students, which had once been relatively high, rose again.

Kurt Maiwald was concerned about the strongly fluctuating number of students, because the financing of the university was tied to this. While the number of students had soared to more than 1,000 in 1923 and the lecturers even had to hold some lectures twice in 1948 because the lecture hall was bursting at the seams, it was only about 400 students in 1953. Finally, the State Central Office for Agriculture in Stuttgart, which had always provided Hohenheim with subsidies, was abolished. A painful financial gap was created.

But Kurt Maiwald did not let this or his critics throw him into a corner. Again and again, voices were raised asking whether fertilizing food was necessary at all. Rudolf Steiner’s “biodynamic farming” was considered an alternative. Kurt Maiwald distanced himself from this in a speech: “If Dr. Ehrenfried Pfeiffer (…) had the fertilizer preparations No. 500 – 508, produced according to anthroposophical thought, spectrographically examined in a North American state institute, this is a worthless analytical dressing up of his text.

His procedure must be rejected from the scientific standpoint because the random origin and uncontrolled pretreatment of the samples he sent for examination are grossly disproportionate to the extremely fine method of analysis applied to them.” He always attached great importance to scientifically proven test results.

Prof. Kurt Maiwald represents Germany at the international OEEC (now OECD)

„It may be that not everything a man thinks is true, for he may err. But in everything he says, he must be truthful. He shall not deceive.“

Immanuel Kant

Professor Maiwald’s youngest daughter

Memories of contemporary witness Dietlinde Dobberthien

“The Hohenheim pedagogical province was what my husband jokingly called it,” Dietlinde Dobberthien recalls. It was all very informal and everyone knew everyone. At that time, the university resembled a large agricultural estate with a horticultural school, cattle stables, horse-drawn carts, ox teams and tractors. There was everything we needed for daily life: A corner store at the then terminus of the Filderbahn, a bakery, a large market garden and, of course, fresh milk.

As a preschooler (my only kindergarten at the time was the Sunday children’s church in what is now the Museum at the Exotic Garden), I went with my mother on daily shopping trips for the family. When we met someone, my mother was addressed as “Mrs. Professor.” She herself had not been allowed to study, although she was a doctor’s daughter. But studies were reserved only for her brothers. So my mother became a chemical-technical assistant and as such met my father. It was all the more astonishing to me how much Margarete von Wrangell deviated from this image of women.

We lived in Margarete von Wrangell’s apartment on the upper floor of the institute. In our house, life took place in our children’s room: we drank coffee on the adjacent balcony, inside my mother studied with us for school, and next to it was the master bedroom. Around the corner came the parlor, on the other side the dining room, kitchen and dining room and everything was heated by the heavy ornate stoves from Wasseralfingen, because there was no central heating yet. In between was a long hallway, which was an attraction for all the professors’ children because there was a pedal car. Below us was my father’s office, and on the floor of the apartment was the lecture hall, which fascinated us children because it was built like an amphitheater.

When family life got too noisy for my father, he would disappear downstairs to his office, which was filled to the brim with books. When central heating was installed in the 1950s, we children secretly lay down on the floor in front of the holes for the heating pipes to listen to how things were checked down there. Of course, we didn’t understand any of the technical jargon. When I was allowed to practice the cello there on weekends, I stood in front of the shelves. My father was particularly fond of Immanuel Kant, and a quote was emblazoned on the wall: “It may be that not everything a man thinks is true, for he may err. But in everything he says, he must be true. He shall not deceive.”

As soon as it rained, there was a bustle outside the Institute. I often stood on the balcony of the Plant Nutrition Institute and watched as the assistants, students and workers ran outside in their white and blue coats and hurriedly drove the carts with the plants under the roof. After all, the measurement results were not to be falsified. Every day, it was precisely documented how much water the plants received.

Doctorates were still something special back then. I remember when my father’s doctoral student was picked up from his viva. They had fixed up an ox cart for him. He had done his doctorate on manure, and on the wagon they had installed an outhouse and around it they had placed birch trees and other trees. The doctoral candidate sat in the outhouse with his doctoral hat, waved to the spectators and was celebrated. So they went through the whole of Hohenheim.

In fact, much of my father’s life revolved around manure. Once I even fell into a manure hole while playing hide-and-seek. I also remember my father arguing with the senior assistant who lived in the apartment diagonally above us. It was about how to justify fertilizing plants. My father always objected to the term “artificial fertilizer” because it was clear to him that fertilizer was derived from natural substances. That is why he preferred to speak of “commercial fertilizer”. It was also very important to him that all students had to do an internship on a farm for two years before graduating. He attached great importance to this, because he never wanted to produce anything only chemically, but always to involve nature.

Dietlinde Dobberthien, jüngste Tochter von Prof. Maiwald erinnert sich als Zeitzeugin

Summer was special for us kids. Then students, professors and their families met in the “academic bathtub” in the botanical garden. That was a small natural swimming pool without chlorine, where I learned to swim. It was always said that every Hohenheim child was once saved from drowning by a student. In addition, the big summer festival was held every year in front of the castle. At that time, Professor Rademacher lived in the castle with his wife and four children. When the festival was coming up, we children were allowed to go to the Rademachers and lie on our stomachs on the intermediate floors. This way we could watch all the dancing. In general, there were regular concerts in the balcony hall. My father loved music and I still remember how the university orchestra and students from the conservatory played together. How proud I was when I was allowed to play for the first time at the age of 17.

I had a very happy childhood and still remember how the Marschners came to Hohenheim in 1960 with their baby and moved into the apartment above us. I also met Professor Michael with his daughter, who later lived in the same apartment building in Steckfeld as my mother. Unfortunately, I lost my parents early. Shortly before his 60th birthday, my father had to go to the hospital. At the time, we didn’t know what was wrong, only that he had had a fall shortly before. I remember my father telling us that he would not return to the university and thinking about his successor: “I hope it’s not someone who only does lab work,” he said. Only a little later he died of an undetected aneurysm close to the heart.

The interview with Dietlinde Dobberthien, born as Maiwald in 1942, took place on May 5, 2023, at the Augustinum Stuttgart-Sillenbuch. As a contemporary witness, Mrs. Dobberthien spoke at the same time on behalf of her three deceased older siblings: Gisela Maiwald (1934 – 2021), Hiltrud von Loewenich, née Maiwald (1936 – 2022), Dr. Dietrich Maiwald (1938 – 2010) and wanted to thank her early deceased parents for a wonderful childhood.

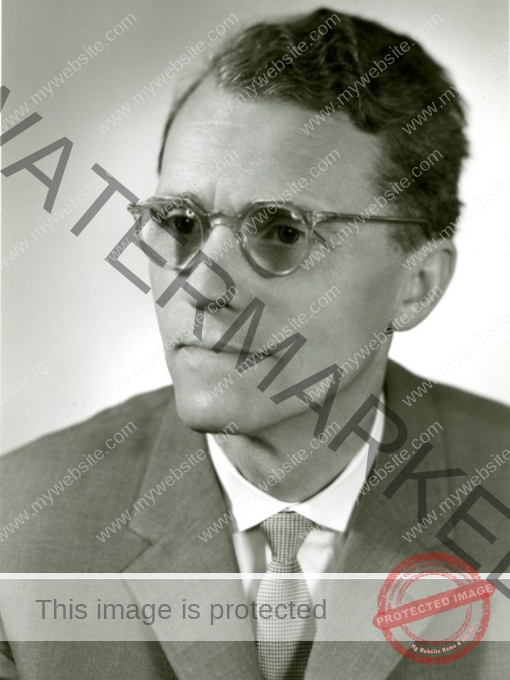

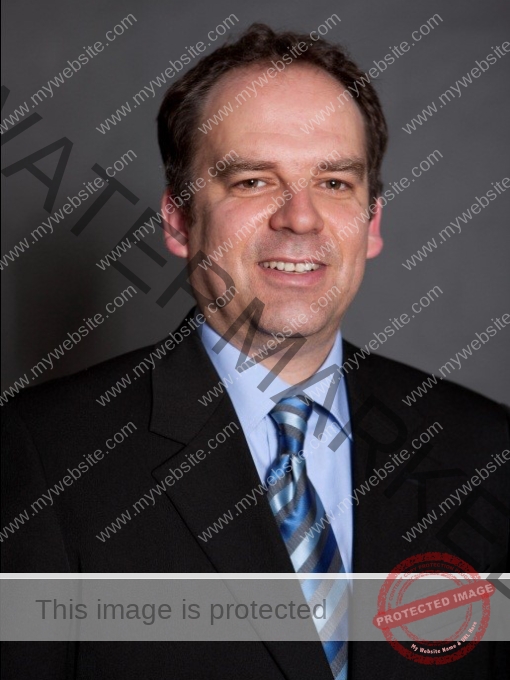

Prof. Gerhard Michael

The institute under Gerhard Michael (1960 – 1976)

Rich harvest in the Cold War

Hardly anyone could inspire with lectures as he did: Professor Gerhard Michael, the third chair holder after Margarete von Wrangell. His passion was legendary, and he was known for appealing to even graduate and doctoral students from neighboring disciplines with his lectures. The supervision of students was always very close to his heart.

After the sudden death of Kurt Maiwald, Gerhard Michael took over the chair and management of the institute in 1960. Previously, he had been a lecturer at the Institute for Plant Nutrition and Soil Biology at Humboldt University in Berlin. However, the political influence of the SED in East Germany got to him. A year before the Wall was built, he left the GDR in 1960 because he believed that the independence of research and teaching was no longer guaranteed there.

For the Federal Republic, the time of food shortages was finally over. Progress in plant breeding, mechanization, land consolidation and mineral fertilization led to overproduction. Thus, under Gerhard Michael, the focus of research shifted to food quality. The main focus was on yields and the composition of fat and protein in harvested products, but also on more accurate measurement methods. Michael introduced isotope technology at the institute and wanted to make scientific methods useful for practical applications. “Do not teach forever What people should think, but How they should think” by Georg Christoph Lichtenberg, was his motto.

He was one of the first agricultural scientists to investigate the movement of nutrients and pollutants in plants and soils using isotope technology and to issue fertilization recommendations. He also investigated the role of phytohormones in plant growth and the influence of environmental factors on the ripening process. As part of a program of the German Research Foundation (DFG), he worked in an interdisciplinary way with scientists on storage processes of crops and the quality of agricultural products.

Four years after his appointment, he became Dean of the Faculty of Agricultural Sciences in the 1964/65 term and remained Institute Director until his retirement in 1976. After his retirement, Gerhard Michael continued to live in a small attic room of the institute and thus remained spatially connected to the University of Hohenheim.

Institute staff under Horst Marschner (1976 – 1996)

The institute under Horst Marschner (1976 – 1996)

Modern technology, environmental awareness and German reunification

Under him, the Institute achieved international recognition: Horst Marschner. Like Kurt Maiwald, the successor to Gerhard Michael had established a wide range of international contacts during study visits to California and South Australia in the 1970s. Horst Marschner’s great goal was to improve people’s living conditions with the help of agricultural research. Together with numerous doctoral students, he primarily investigated the complex problems of adapting agricultural crops to nutrient-poor soils.

Horst Marschner was particularly interested in China. After the Cultural Revolution, he and Erwin Martin Reisch were among the first generation of foreign researchers to establish and maintain contact with Chinese colleagues. For this, Horst Marschner was honored by the Chinese government with the highest award for foreign experts.

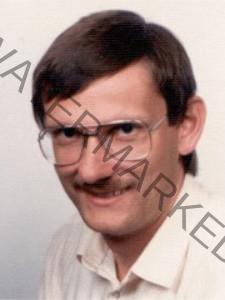

Prof. Horst Marschner

Horst Marschner liked to work in an interdisciplinary way and also led international research groups together at the institute. He himself participated in land cultivation projects in Turkey and West Africa.

What particularly interested him were the root hairs, the mycorrhiza, and how the uptake of nutrients and their transport took place in the plant. Horst Marschner mainly investigated phosphorus, cesium, zinc and iron and was able to use modern analytical methods and laboratory technology for this purpose. The further development of computer technology greatly simplified the international exchange of research results. At the same time, environmental awareness grew in society, and the contamination of soils by heavy metals or water pollution came into focus.

For Horst Marschner, a visit to an agricultural research project in West Africa proved fatal. After his return, he died unexpectedly in 1996 as a result of a malaria infection at the age of 66.

Institute staff under Nicolaus von Wirén (2001 – 2010)

Prof. Nicolaus von Wirén

The institute under Nicolaus von Wirén and his successors (1996 – 2023)

Fascination in miniature: The world of molecules and micronutrients

Delving deeper into the details. This could summarize the research at the Institute for Plant Nutrition since 1996. In 2001, the young scientist Nicolaus von Wirén, who conducted research in the field of molecular biology, was appointed to the “von Wrangell” chair as the successor to Horst Marschner. Nicolaus von Wirén focused on nutrient uptake through the roots and plant nutrient efficiency.

When he moved to the Leibniz Institute of Plant Genetics and Crop Plant Research (IPK) Gatersleben, Uwe Ludewig followed him in 2010 for the Department of Nutritional Physiology of Cultivated Plants, which he still heads today.

Uwe Ludewig is mainly concerned with transport processes at the roots and in plants. In particular, he investigates how the transport of nutrients such as ammonium, nitrogen or phosphorus is regulated via cell membranes. Uwe Ludewig wants to understand the genetic and molecular basis of nutrient uptake and distribution in order to make crops fit for climate change and reduce fertilizer consumption.

The more specialized the research at the Plant Nutrition Institute became, the more it grew. Since Margaret von Wrangell’s founding, new areas of expertise have been added and are now united in the Institute of Crop Sciences.

Institute staff under Uwe Ludewig

The institute under Uwe Ludewig (since 2010)

Diverse Research

Phosphate continues to play an important role in current research, just as it did for Margarete von Wrangell. Professor Torsten Müller from the Department of Fertilization and Soil Matter Dynamics chair and Professor Uwe Ludewig are investigating how phosphate can be recovered from bio-waste, domestic wastewater, or residues from biogas plants. After just over 100 years, the world’s phosphate reserves could soon be exhausted.

It is all the more important to establish a sustainable circular economy for phosphate in the spirit of bioeconomy. In this way, the institute remains true to its origins to this day.

The increased importance of the Plant Nutrition Institute is also reflected in the number of professors who were appointed in addition to Margarete von Wrangell’s direct successors:

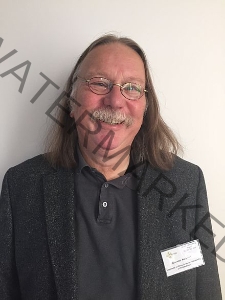

Prof. Uwe Ludewig

Walter J. Horst

1981-1987

Norbert Claassen

1990-1991

Volker Römheld

1992-2008

Sven Schubert

1992-1997

Torsten Müller

seit 2004

Günter Neumann

seit 2010

More Information

More information about the history of agriculture in Germany can be found on the website of the German Agricultural Museum of the University of Hohenheim.

Quellen

1818 – 1953 from “Development of an Agricultural University” (at the ceremonial act 20.11.1953) On November 20, 1818, the agricultural lectures of the Agricultural Institute Hohenheim began.

Modified from Hamann, Helena (2011): The History of the Institute for Plant Nutrition at the University of Hohenheim. Master’s thesis, Inst. for Crop Science, University of Hohenheim, p. 102.

“Soil Biology and Plant Nutrition facing new challenges”, speeches by Dr. Kurt Maiwald and Dr. Bernhard Rademacher, Agricultural University of Hohenheim, Speeches and Treatises, Issue No. 5, published by Eugen Ulmer Verlag, Stuttgart / currently Ludwigsburg.

“History of the Institute for Plant Nutrition”, poster by Helena Hamann, Uwe Ludewig, Jochen Streb, Torsten Müller, and presentation