Anniversary lecture as part of the annual conference of the German Society for Plant Nutrition (DGP) on 25.09.2023 at the Euroforum of the University of Hohenheim

100 years of the Plant Nutrition Institute: Research then and now

The German Society for Plant Nutrition (DGP) has been committed to research and teaching since 1968. At this year’s annual conference at the University of Hohenheim from September 25 to 27, 2023, Professor Uwe Ludewig gave a special lecture: “Plant nutrition then and now”.

In it, he took a look back at the founding of the Plant Nutrition Institute by Margarete von Wrangell, showed what the professor initiated and achieved and drew a line to the current research topics at today’s Institute of Crop Sciences.

Prof. Uwe Ludewig

What happened 100 years ago and still has an impact today

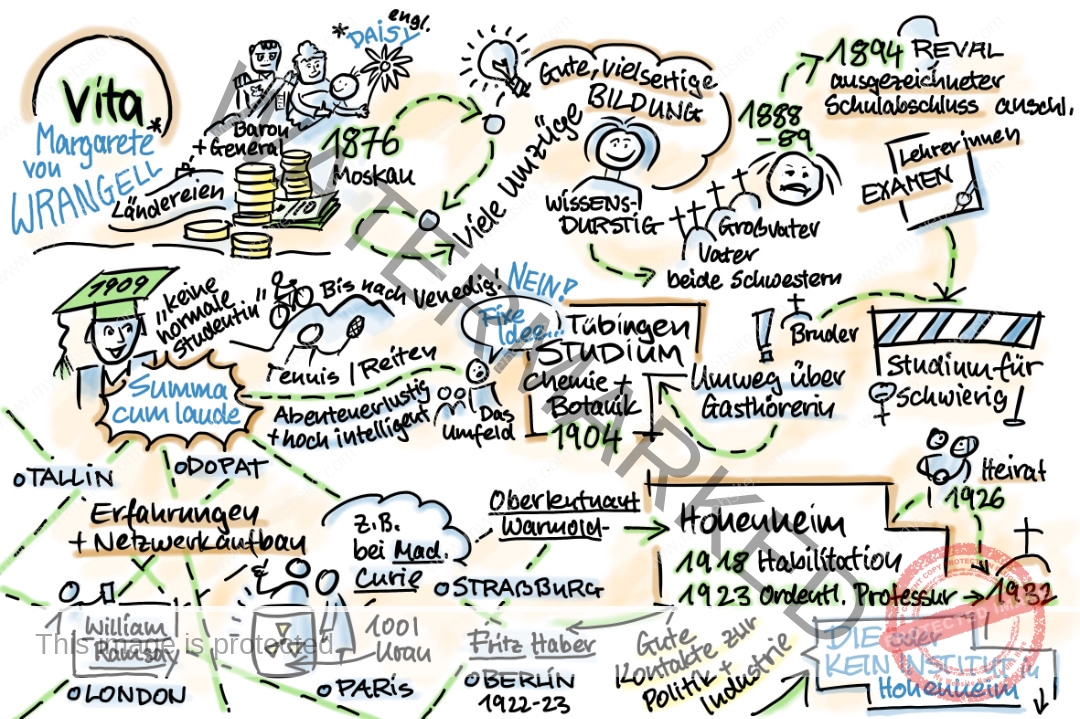

Margarete von Wrangell not only became Germany’s first female professor in 1923, she also founded the Institute of Plant Nutrition at what was then Hohenheim Agricultural College, now the University of Hohenheim. Professor Uwe Ludewig began his anniversary lecture with a historical overview of the founding of the institute using a timeline. Historical events such as the two world wars had an influence on research, as did the social structures of the time. Margarete von Wrangell was an exception among scientists and was one of the privileged.

Uwe Ludewig summarized why she was able to pursue a career in science even though women were forbidden to work at the time. She was aristocratic, financially independent and was brought up in such a way that she gave instructions to servants from an early age. These qualities helped her on her way to becoming a professor.

Margarete von Wrangell also had a good network to fall back on: she was acquainted with Hermann Warmbold, Fritz Haber and Friedrich Aereboe – influential personalities of her time who supported her on her path to becoming a professor. Uwe Ludewig recalled: “It was not until 1977 that the law in West Germany was changed so that women were allowed to work without their husband’s permission.”

When asked whether a career like Margarete von Wrangell’s was still possible today, he referred to the Academic Fixed-Term Contract Act. This law means that only a very limited amount of time is available for academic work after a doctorate. “Too little in my opinion,” said Ludewig. “Because we will need both specialists and generalists in the future – that’s why interdisciplinary research is so important.”

Uwe Ludewig also paid special tribute to one of Margarete von Wrangell’s successors: Horst Marschner. His textbook is still regarded as the “bible of plant nutrition” and is now in its 4th edition. Between 1976 and 1996, he worked at the University of Hohenheim and established many international contacts. The subsequent change of name of the “Institute of Plant Nutrition” to the “Institute of Crop Sciences” shows how the view of researchers has broadened.

„There is still a clear male dominance in management positions in the agricultural sector.“

Prof. Uwe Ludewig

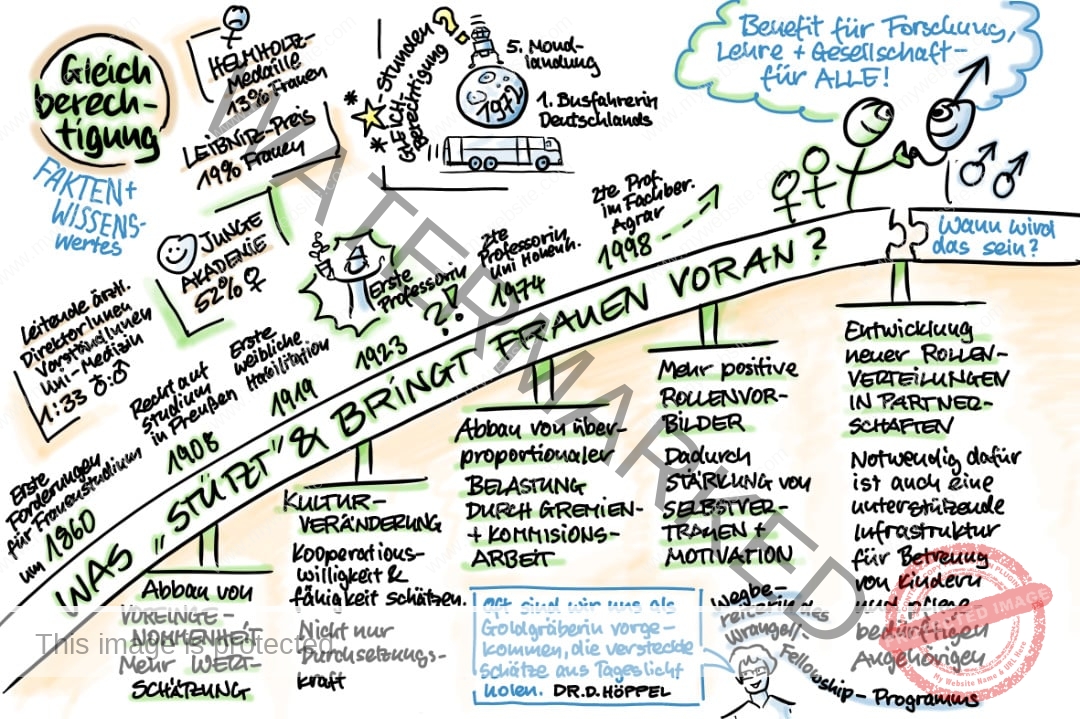

The role of women in current research

In a recent photo, Professor Ludewig showed what the proportion of female professors at the university looks like today. A male dominance can still be seen, but a third of professors today are female. The proportion of female students completing degrees is even over 50 percent.

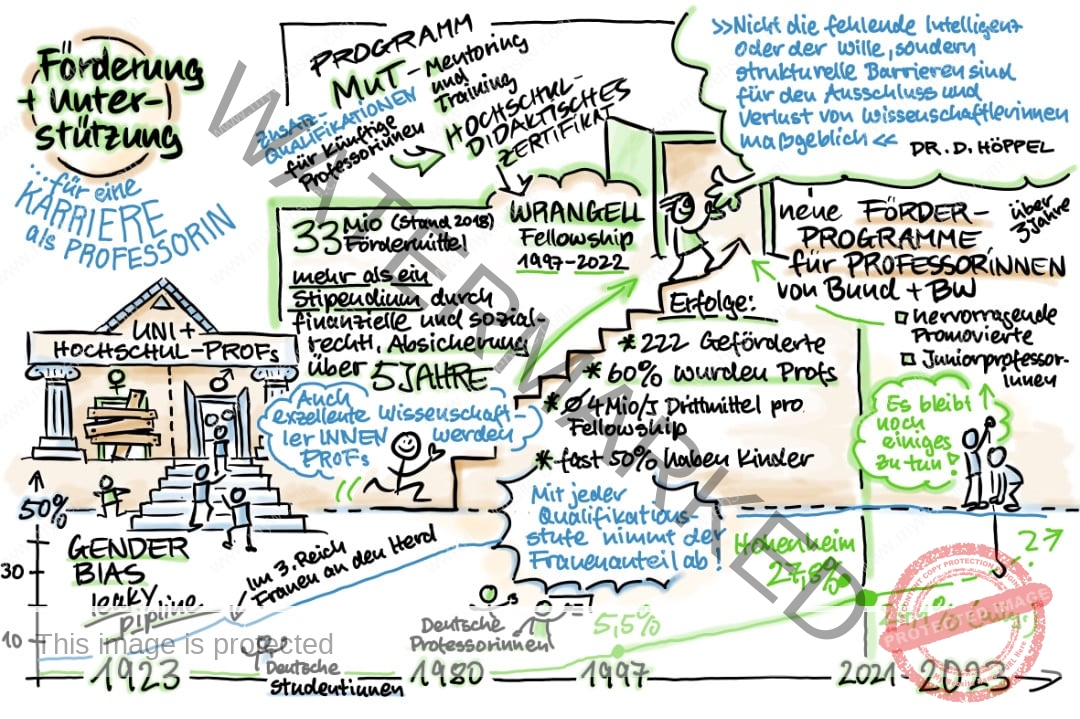

“We have already reached 50 percent of junior professorships in the tenure-track program in Baden-Württemberg,” said Ludewig. This made it clear to him: “The imbalance in the professorate will soon grow out.” In this context, Uwe Ludewig cited the Margarete von Wrangell Fellowship as an example of success.

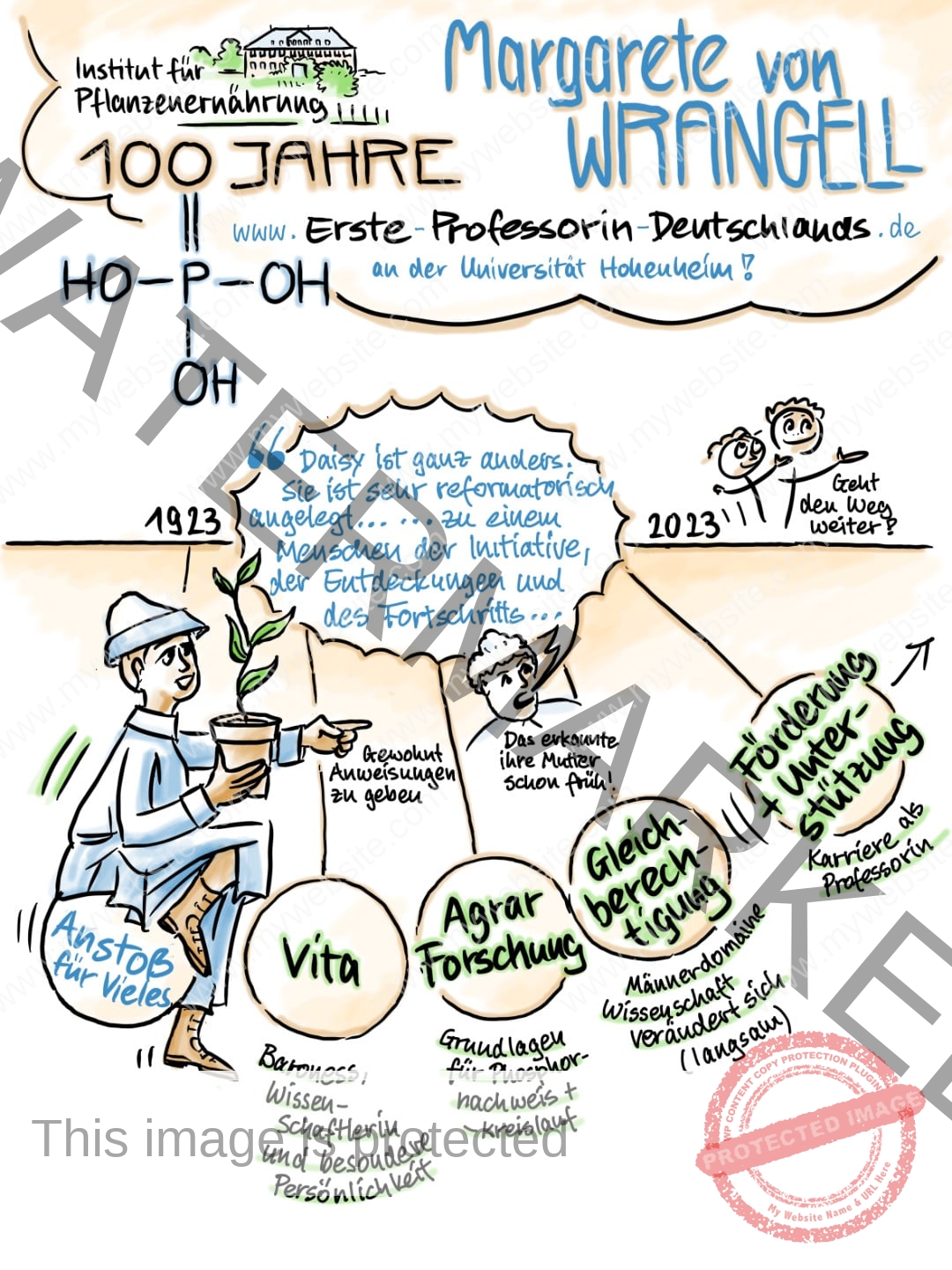

The life and work of Margarete von Wrangell in sketchnotes

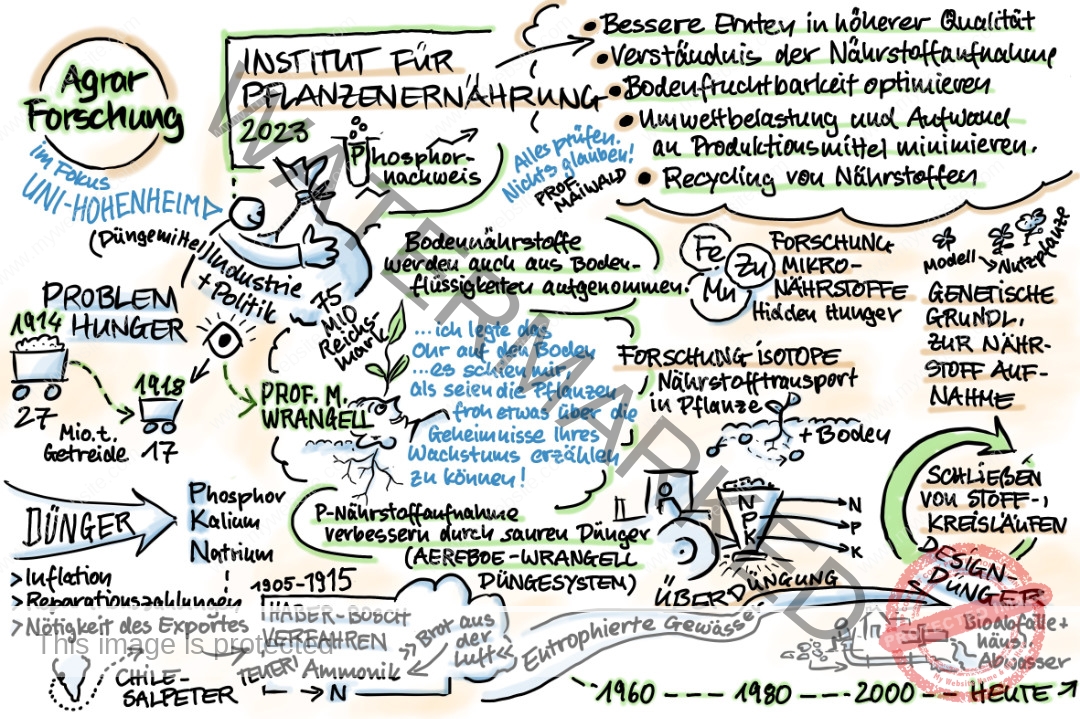

Phosphorus – a problem that has not yet been solved

Uwe Ludewig then turned his attention to the present day. Two elements are still the focus of scientists because they are important for plant nutrition: nitrogen and phosphorus. Uwe Ludewig summarized what nutrient solution trials, pot trials and field trials have shown: While nitrate reaches deeper soil layers with the rain, phosphorus remains on the surface and is not very mobile in the soil. Despite a high phosphate content in the soil, phosphorus is therefore poorly usable for plants.

It is usually present in absorbed or precipitated forms of phosphates and therefore cannot be readily absorbed by plants. “Complex chemical processes take place in the soil that are dependent on temperature, microbes or the degree of mineralization.” Margaret von Wrangell was already aware of this limited availability of phosphorus 100 years ago.

However, there are processes that improve phosphorus uptake. For example, symbiosis with fungi, known as mycorrhiza. Special cluster root structures, such as those of the white lupin, also increase phosphorus uptake. In contrast, the determination of nitrogen requirements from the soil and nitrogen uptake are unproblematic, but in practice there are still enormous sources of loss. Since the development of the Haber-Bosch process in 1910, nitrogen for fertilizers can be obtained from atmospheric nitrogen and is therefore available in almost unlimited quantities.

He concluded that phosphorus is still an exciting research topic. “Due to the complex chemical properties of phosphorus, we are still unable to make precise predictions about its availability in the soil.”

The surprising results of long-term trials

Laboratory trials under controlled conditions are one thing – but the results of field trials are crucial for agricultural practice. This is why a transnational team of researchers in Germany and Austria carried out long-term trials on phosphorus fertilization.

Uwe Ludewig explained the measurement methods used to classify the soils into content classes A to E, where A stands for a low phosphorus content and E for a high phosphorus content. The researchers expected the highest yield increases for content class A through phosphorus fertilization of the soil and little or no yield increases for content class E.

However, the results were surprising. While some plants grew better after phosphorus fertilization, others had the opposite effect. “On different soils of the same content class, we saw yield increases of 50 percent and simultaneous losses of 15 percent. These large fluctuations show that fertilizer recommendations with regard to phosphorus remain difficult.”

How Hohenheim is preparing agriculture for climate change

In addition to phosphorus research, scientists at the institute are also focusing on climate change and extreme weather events. Uwe Ludewig presented results from the earlier “BIOFECTOR” project, which aims to promote soil fertility through biological processes. The so-called bioeffectors include bacteria or biostimulants. Previous results have shown that bioeffectors often have positive effects under controlled conditions, but rarely in field trials. The researchers now want to find out why this is the case.

Uwe Ludewig also reported on the interdisciplinary “AMAIZE-P” project with maize plants that are to be adapted to limited phosphorus resources. “Older varieties sometimes show much better phosphate utilization,” explained Ludewig. This is why the scientists are working together with breeders. They are also trying to recycle phosphorus from animal and human excrement and bones. This could replace up to 60 percent of raw phosphates. “Recycling raw materials is the way we should deal with limited resources,” said Ludewig.

Finally, Uwe Ludewig presented the “NOcsPS” project. An interdisciplinary team from the University of Hohenheim is researching a cultivation method that does not require the use of synthetic chemical pesticides. Ludewig called this system Agriculture 4.0. “With NOcsPS, we achieve up to 50 percent higher yields than in organic farming and positive ecological effects. This could be our agricultural system of the future.”

How the research landscape has changed

Finally, Ludewig took a look at the Institute of Crop Sciences. With the merger of different research areas, the institute has become more diverse. In the meantime, not only nutrients, but also their transport processes in the plant as well as genetic and molecular principles and the root system including soil microbes are being examined.

According to Ludewig, this comprehensive understanding and basic research are the prerequisites for tackling climate change. “If we know where to start, we can use CRISPR gene scissors to make crops fit for climate change.”

Uwe Ludewig thus closed the circle on the topic of women’s careers. The CRISPR gene scissors were discovered by Jennifer Doudna and Emmanuelle Charpentier, who were awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2020.

In conclusion, Uwe Ludewig drew a clear conclusion: in the past, special circumstances had to come together for women to make a career in science. Today, there is equal access to educational and management positions. Gender no longer plays a role in the success of scientists. It is much more important that plant nutrition has socially relevant knowledge to offer for the future, especially for our food security.

Lecture in honor of Prof. Dr. Margarete von Wrangell

Sources and links

The lecture took place on 25.09.2023 at the Euroforum of the University of Hohenheim.